Content:

- GPU Architecture

- Block scheduling:

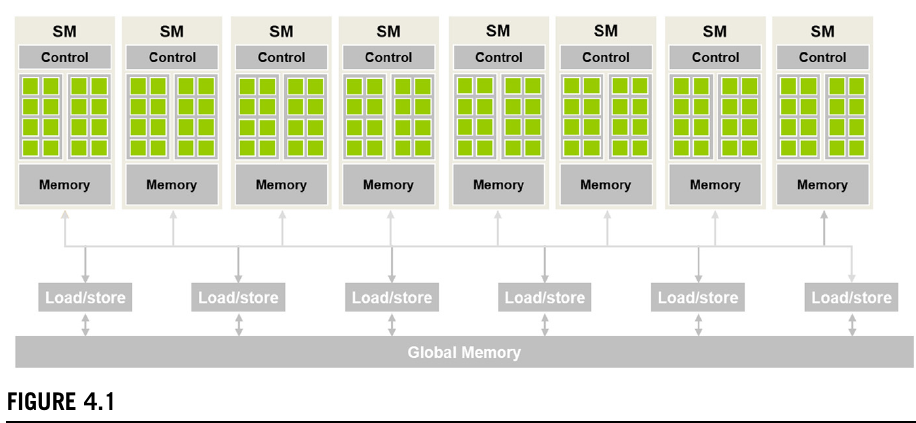

GPU architecture:

- GPUs are organized into an array of highly threaded SMs (Streaming Multiprocessors).

- Each SM contains:

- GPU cores (processing units)

- Control units (manage instruction fetching, scheduling, and execution flow)

- Shared Memory (on-chip) (accessed and shared between threads of the same blog)

-

Cores inside the same SM share the same control logic and memory resources.

- All SMs have access to global memory (DRAM) (off-chip).

Block scheduling:

-

A kernel launches a grid of threads that are organized in thread blocks. Each thread block is assigned to the same SM. But, multiple blocks are likely to be assigned to the same SM.

-

Before execution, each block must reserve the necessary hardware resources, such as registers and shared memory. Since the number of thread blocks typically exceeds what a single SM can handle simultaneously, the runtime system maintains a queue of pending blocks. As SMs complete execution of current blocks, new blocks from the queue are assigned to them.

- This block-by-block assignment simplifies coordination for threads under the same block, by using:

- Barrier synchronization.

- Accessing a low-latency shared memory that resides on the SM.

- Note: Threads in different blocks can perform barrier synchronization through the Cooperative Groups API.

Synchronisation and transparent scalability:

-

The

__syncthreads()function ensures that all threads within a block reach the same point before any proceed further. The threads that reach the barrier early will wait until all others have arrived. -

__syncthreads()must be called by all threads in the block. Placing it inside an if-else block (where threads diverge) can lead to deadlocks, or undefined behavior. - When using barrier sync, threads (of the same block) should execute in close time proximity with each other to avoid excessively long waiting times.

- The system needs to make sure that all threads involved in the barrier synchronization have access to the necessary resources to eventually arrive at the barrier.

- Not only do all threads in a block have to be assigned to the same SM, but also they need to be assigned to that SM simultaneously. That is, a block can begin execution only when the runtime system has secured all the resources needed by all threads in the block to complete execution.

- CUDA runtime system can execute blocks at any order (none of them need to wait for each other). This flexibility enables transparent scalability, i.e., the ability to execute the same code on different devices. Not requiring threads across different blocks to sync makes it easier to change order or execution from one device to another, and how many blocks are processed simultaneously.

Warps and SIMD hardware:

-

Now we focus on threads of the same block. Threads can be executed at any order with respect to each other.

-

In algorithms with phases (all threads have to be at the same level), one should use barrier sync to impose that.

-

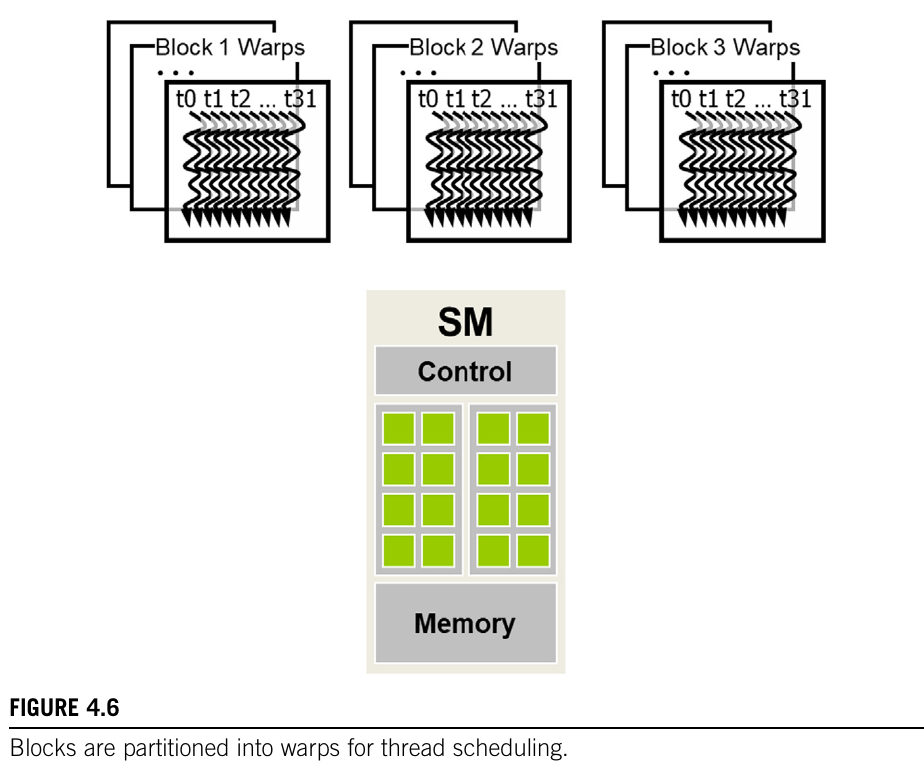

A warp is a unit of thread scheduling in SMs, and are executed SIMD style.

-

Once a block has been assigned to an SM. Is it divided into warps (units of 32 threads of consecutive

threadIdx, what if there was multi-dim blocks?).- If blocks are multi-dim, the dimensions will be linearised first, row major layout.

Within each thread block assigned to an SM, threads are further organized into warps. A warp is the fundamental unit of thread scheduling in NVIDIA GPUs, consisting of 32 threads executed in a Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) fashion. Here’s how warps function within the GPU architecture:

-

Warp Formation: Once a thread block is assigned to an SM, it is divided into warps of 32 consecutive threads based on their threadIdx. For multi-dimensional thread blocks, thread indices are linearized in a row-major order before warp formation.

-

Handling Non-Multiples of Warp Size: If a thread block size is not a multiple of 32, the final warp is padded with inactive threads to complete the 32-thread structure. These inactive threads do not participate in execution, ensuring uniform warp processing.

-

SIMD Execution: An SM fetches and executes a single instruction for all active threads within a warp simultaneously. Each thread in the warp processes different data elements, enabling high throughput for parallel workloads.

-

Processing Blocks within SMs: Modern GPUs, such as the NVIDIA A100, divide each SM into smaller processing blocks. For instance, an A100 SM contains 64 CUDA cores, which are grouped into 4 processing blocks of 16 cores each. Warps are assigned to these processing blocks, allowing multiple warps to be active within an SM and facilitating efficient instruction dispatch and execution.

-

Resource Efficiency: By grouping threads into warps and executing them in lockstep, GPUs minimize the resources required for control logic. All threads in a warp share the same instruction stream and execution order, reducing the complexity of the scheduling hardware.

Parallel to the VN computer model:

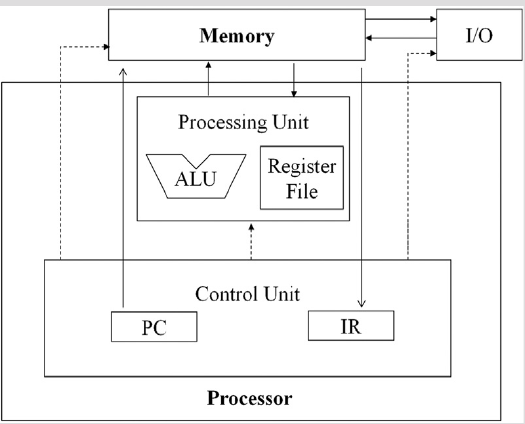

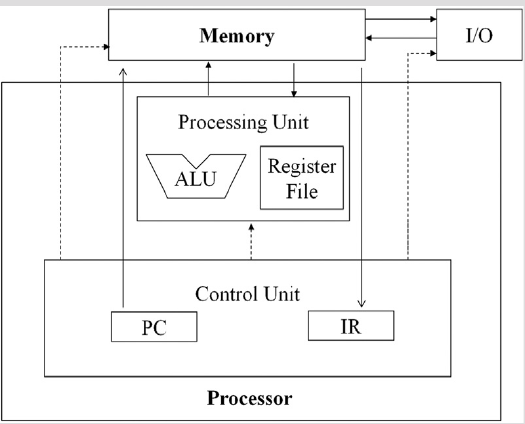

The von Neumann computer model:

Executing threads in warps reflects upon this model:,

Some notes on the analogy:

- A processor is a processing block

- A processing unit is a core a of processing block.

- Cores of the same processing block receive the same control signals.

- Warps are assigned to the same processing block, and executed SIMD style.

Control divergence:

-

SIMD work best when all threads follow the same control flow.

-

When threads within the same warp take different paths (some go through an if, some go through an else). The SIMD hardware will take multiple passes. One through each path. During each path, the threads that do not follow the path are not allowed to take effect.

-

If threads following different control flow, we say: “threads exhibit control divergence”.

-

In PASCAL architecture, these passes are executed sequentially, one after another. From Volta Architecture onwards, the passes may be executed concurrently. The latter feature » independent thread scheduling.

-

To ensure that all threads of a warp sync use:

__syncwarps().

Warps scheduling and latency tolerance:

-

An SM can execute instructions for only a small number of the warps that are assigned to it at once.

- Why assign more warps than capable of? This is a feature and not a bug. This is how GPUs hide long-latency operation, such as global memory access. Often referred to as latency hiding:

- When an instruction to be executed by a warp needs to wait for the result of a previously initiated long-latency operation, the warp is not selected for execution.

- Instead, another resident warp that is no longer waiting for results of previous instructions will be selected for execution.

- If more than one warp is ready for execution, a priority mechanism is used to select one for execution.

-

The selection of ready-to-go warps does not introduce any additional wasted time > zero-overhead thread scheduling.

-

This ability to hide latency by switching between warps, is why GPUs do not need any sophisticated mechanisms like advanced control logic, cache memories and so on (how CPUs work), hence, again, GPUs can dedicate more on-chip area to floating-point execution and memory access channel resources.

-

Zero-overhead scheduling: The GPU’s ability to put a warp that needs to wait for a long-latency instruction result to sleep and activate a warp that is ready to go without introducing any extra idle cycles in the processing units.

-

In CPUs, switching the execution from one thread to another requires saving the execution state to memory and loading the execution state of the incoming thread from memory.

-

GPU SMs achieves zero-overhead scheduling by holding all the execution states for the assigned warps in the hardware registers so there is no need to save and restore states when switching from one warp to another.

- For an A100, is it normal to have a ratio of 32 threads per core, i.e., 2048 threads per SM.

Resource partitioning and occupancy:

- Occupancy = number of warps assigned to an SM / maximum number it supports.

-

How SM resources are partitioned:

- SM execution resources (for an A100):

- Registers

- Shared memory

- thread block slots

- thread slots (2048 in each SM)

-

These resources are dynamically partitioned, for an A100, block size could vary between 1024 and 64, leading to 2-32 blocks per SM.

-

Some kernels may use many automatic variables. Hence, threads may have to use many registers. Leading to the SM accommodating variant number of blocks at once, depends on how much registers they require.

-

For an A100, it has 65k registers per SM. To run at full capacity, each thread should be satisfied with 32 registers.

-

In some cases, the compiler may perform register spilling to reduce the register requirement per thread and thus increase the occupancy. May add some additional execution time for the thread to access the spilled registers.

-

The fuck is a spilled register? »

- Check the CUDA Occupancy Calculator.

Querying device properties:

- The CUDA runtime API provide a built-in C struct cadaver’s with many interesting fields to query the device properties as shown below:

- Running the following code:

int main(){

int devCount;

cudaGetDeviceCount(&devCount);

std::cout << "Number of CUDA devices: " << devCount << std::endl;

cudaDeviceProp devProp;

for (int i = 0; i < devCount; i++){

cudaGetDeviceProperties(&devProp, i);

std::cout << "Device " << i << ": " << devProp.name << std::endl;

std::cout << "Compute capability: " << devProp.major << "." << devProp.minor << std::endl;

std::cout << "Total global memory: " << devProp.totalGlobalMem << std::endl;

std::cout << "Shared memory per block: " << devProp.sharedMemPerBlock << std::endl;

std::cout << "Registers per block: " << devProp.regsPerBlock << std::endl;

std::cout << "Warp size: " << devProp.warpSize << std::endl;

std::cout << "Max threads per block: " << devProp.maxThreadsPerBlock << std::endl;

std::cout << "Max threads dimensions: " << devProp.maxThreadsDim[0] << " x " << devProp.maxThreadsDim[1] << " x " << devProp.maxThreadsDim[2] << std::endl;

std::cout << "Max grid size: " << devProp.maxGridSize[0] << " x " << devProp.maxGridSize[1] << " x " << devProp.maxGridSize[2] << std::endl;

std::cout << "Clock rate: " << devProp.clockRate << std::endl;

std::cout << "Total constant memory: " << devProp.totalConstMem << std::endl;

std::cout << "Texture alignment: " << devProp.textureAlignment << std::endl;

std::cout << "Multiprocessor count: " << devProp.multiProcessorCount << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

Will return the following on my A100 remote machine:

$ nvcc -o props props.cu

$ ./props

Number of CUDA devices: 1

Device 0: NVIDIA A100 80GB PCIe

Compute capability: 8.0

Total global memory: 84974239744

Shared memory per block: 49152

Registers per block: 65536

Warp size: 32

Max threads per block: 1024

Max threads dimensions: 1024 x 1024 x 64

Max grid size: 2147483647 x 65535 x 65535

Clock rate: 1410000

Total constant memory: 65536

Texture alignment: 512

Multiprocessor count: 108A

- Compute Capability is a versioning system used primarily by NVIDIA to define the features and capabilities of their GPU architectures, for example:

- 7.x: Corresponds to the Volta architecture (Introduced Tensor core, and so on).

- 8.x: Relates to the Ampere architecture.

- 9.x: Pertains to the Hopper architecture.